A brief history of the restorative garden

One of our Gardens and Health beneficiaries is Maggie’s. Built alongside NHS hospitals, their centres are uplifting places with professional staff on hand to offer the support people with cancer and their families need. They combine iconic architecture with gorgeous gardens. The following extract comes from a study commissioned by Maggie’s Resilient Places? Healthcare Gardens and Maggie’s Centres by Angela Butterworth and looks at the rise and fall of gardens for health in history…

The health benefits of gardens have been appreciated as far back as 600 BC. Indeed throughout history and within most cultures, there have always been gardens (and plants) associated with healing.

The belief that contact with trees, grass and flowers fosters wellbeing and helps to reduce the stress of urban living is evident in ancient Egyptian, Persian, Greek and Roman culture. There is also a long history of creating gardens attached to places of healing or spiritual care.

Although the maintenance of gardens in hospitals has not been consistently championed throughout history, there has usually been a commitment to the experience and experimentation with outdoor green space within the healthcare context. Gardens have always had a role in humane medical care.

Asclepieia

In Egypt and Greece gardens were closely associated with medicine. At least since the fourth century BC to the sixth century AD Greece had healing centres or Asclepieia devoted to the god of medicine and healing, Asclepius. Asclepieia, places where Asclepius was believed to heal, could be found throughout the ancient world. One of the most famous shrines was the sanctuary at Epidaurus in the Eastern Peloponnese.

The sanctuary is in a secluded spot in rolling hills with a good water supply and beautiful scenery. Archaeological research shows the topography of the site combined with a unique configuration of buildings and green space. As a historical site it contributes to an understanding of gardens and health. It was regarded as sacred and this was an important part of the creation of a healing environment.

The Enclosed Garden

Enclosure has been central to many types of gardens across the world including the Persian pleasure garden, the Islamic chahar-bagh, the Roman courtyard, Chinese and Korean courtyard gardens and Japanese dry rock gardens. While such enclosed spaces were primarily dictated by climate or the need for physical protection, they also embodied the idea of restoration.

In medieval Europe the hortus conclusus or enclosed garden, derived from the Roman courtyard, generally provided a safe haven, a calm and quiet breathing space separated from the chaos of city life or the unsafe countryside. And enclosed restorative gardens were intimately connected with the European medieval monastery.

Gardens adjoining institutions for the care of the poor, sick and infirm were commonplace and known to be integral to the daily routines and rhythms of institutions. Monastic practices combined popular herbal remedies and dietary prescriptions with Classical Greek medical theory emphasising the close relationship between health and the environment.

Most monasteries included medicinal gardens next to the infirmary, reflecting the fact that botany was closely allied with the practice of medicine in the Middles Ages. They were also places for contemplation, gentle recreation and spiritual regeneration. Set within the grounds of the monastery beyond the city walls these early institutions linked to the ancient idea of the pantheistic Asclepieia or sanatorium in its rural idyll. The rise of cities in the Middle Ages meant that hospitals became increasingly connected to urban life.

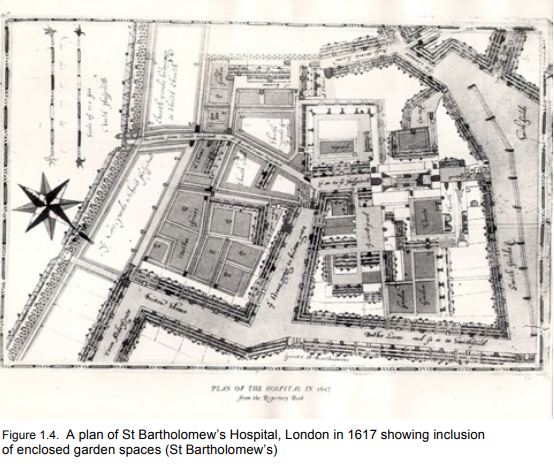

In England, hospitals such as St Bartholomew’s (1123) and The Savoy (1505) in London or St Giles in Norwich (1249) included spaces such as a walled herb garden, a kitchen garden, orchards and a ‘paradyse’ garden where inhabitants were able to engage in quiet contemplation. This latter space, common to most establishments, was modelled on the central cloister of the monastery.

The enclosed or courtyard garden is found in the first hospitals in Britain. The use of cloisters functioned not just as an architectural feature linking building and garden and all the activities of the hospital, but provided access to fresh air whilst providing protection from wind and rain.

Although the tradition of the courtyard garden is more often associated with a hotter climate than the UK, enclosed gardens have always been important, first within the monasteries and then as botanic and ‘physik’ gardens and eventually as the walled kitchen garden.

Sensory refreshment

In the medieval and early modern period it was generally believed that because gardens could refresh the senses, they had an impact on health. The importance of fresh clean air and scent upon human physiology and psychology was particularly stressed.

Colour was also thought to have a profound effect upon mind and body and green was widely believed to soothe, refresh and nourish the eyes. Thus the health giving properties of lawns and meadows were considered and this perhaps explains why many people chose to study in gardens. In monasteries books were often stored in carrels (small cubicle or enclosure with a desk for study) around the cloister where monks would sit and read surrounded by green turf.

The distinction between the healthy countryside and unhealthy towns is reflected in the writings of key figures in garden history. Thomas Hill’s The Gardeners Labyrinth (1577:25), argued that gardens were crucial to health and mental wellbeing. His book lists many remedies for a ‘wearied mind’ and ‘dull spirites’ and he writes of what is to be gained from the ‘delectable sightes’ of a ‘beautifull and Odiferous Garden’.

The secularisation of hospitals and the decline of the monastic paradise garden signalled the decline, though not disappearance, of restorative gardens. Hospitals remained prominent, even pivotal architectural elements of European cities, but the (premium) green space within and around them became less valued.

Today, this recognition of the importance of gardens and green spaces for good health, wellbeing and recovery from illness is returning to the fore. Their creation and use is championed through the National Garden Scheme’s Gardens and Health programme and beneficiaries including Maggie’s – who we thank for sharing this extract. Horatio’s Garden and many of the smaller community gardens that our funding supports are all important, modern restorative gardens for many.

This article was originally published in The Little Yellow Book of Gardens and Health

To find out when Maggie Centre gardens open for the National Garden Scheme this year CLICK HERE

- Maggie’s, Manchester